Frustum Culling

December 24, 2020Update: After posting this on twitter, I received a few helpful suggestions to implement a more robust testing using the separating axis theorem. I’ll implement and write up a follow up post soon, but I wanted to post this disclaimer that perhaps I was a bit too optimistic on just how many false negatives this method would produce. I’ll include a more detailed explanation in the follow up.

Introduction

It’s been a while! As it has been for many, 2020 has been a bit of a rollercoaster for me. Also at some point I decided to try and write my own DX12 rendering lib from scratch, and it was maybe ill advised from a “productively implement graphics techniques” perspective, but it’s definitely forced me to read and write a lot more C/C++ code. But I digress, since that’s not what this post is about and instead we’ll be talking about how to reduce wasted work rendering objects out of view.

But before we get started, let’s review what happens when you submit a draw call for a mesh that’s not visible from the camera’s point of view: first, we’ll have to record the associated information into a command buffer such as pointers to the meshes we’re rendering, any changes in pipeline state, texture pointers and material data, etc. Recording and submitting this data is relatively cheap using DX12, but not free. The command buffer is then copied and sent over to the GPU through your PCIe bus, at which point the GPU command processor can start consuming it.

The first stage in the pipeline is going to be input assembly (IA) where we load indices from the mesh’s index buffer (if applicable) as well as the associated vertex data, which are then passed to our vertex shaders. This second stage is chiefly responsible for transforming our vertices into clip space, calculated using the model, view and projection transforms that we’ve passed in from the CPU side of our application. With that work done, the next stage, called primitive assembly (PA), groups our vertices into the primitive type set by our pipeline state (e.g. points, lines or triangles) and performs viewport and backface culling, as well as clipping of any primitives that intersect the boundaries of NDC space.

For a visible mesh, there are additional stages but this is the end of the line for our non-visible meshes since they will be entirely culled by the viewport culling, resulting in an early exit. If you’re interested in a more exhaustive overview of the pipeline, I recommend this series of blog posts by Fabian Giesen. The point is that none of this work I just described will result in pixel writes and it is just a waste of time.

Additionally, we should also consider that we often render the same scene from multiple points of view. For example, when rendering shadow maps we’re going to pay this tax for each map we’re rendering to.

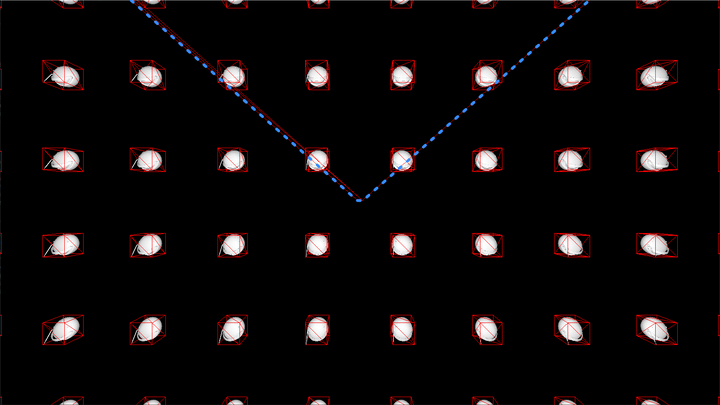

Obviously we’re performing a ton of extra work that is totally useless. To demonstrate this, I set up a scene with 10,000 Boom Boxes arranged in a 3D grid around the origin. The data associated with their draw calls is stored in linear arrays that we loop through during our render pass, so it’s as simple as I could make it. The camera sits in the middle of the 3D grid, seeing only a subset of the boomboxes. Here’s an overhead view of the scene (with only a subset of boomboxes rendered, to make it cleaer):

All the meshes being rendered behind the blue line that represents our view frustum represent wasted work! Naively rendering all 10,000 of these meshes on my PC resulted in the following timings:

| Task | Timing (ms) |

|---|---|

| CPU Command Buffer Creation + Submission | 2.4 |

| GPU execution | 5.8 |

| Total | 8.2 |

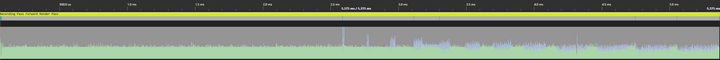

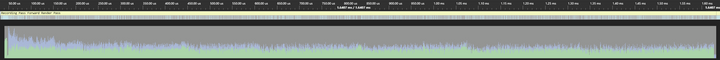

We can get a sense of how much time is being wasted by examining the GPU occupancy graph which displays a timeline of how our GPU was utilized during the frame, specifically indicating the number of waves/warps being run in parallel per SM. The green indicates that the warps are being used for vertex shading, while the light blue indicates that they’re being used for pixel/fragment shading.

The graph shows that ~5.6 ms are required to render all our meshes, but we spent the majority of that time running the vertex shaders for geometry that has no corresponding pixel shading (to be clear, this is indicated by the large regions of vertex shader work without any corresponding pixel shader work, in blue). This means we should expect large gains on the order of 3-4 ms if we are able to selectively render only objects in view.

A solution seems obvious: don’t try to render objects out of view! That should mean fewer commands, which should mean less wasted time on both the CPU and GPU.

Culling and Bounding Volumes

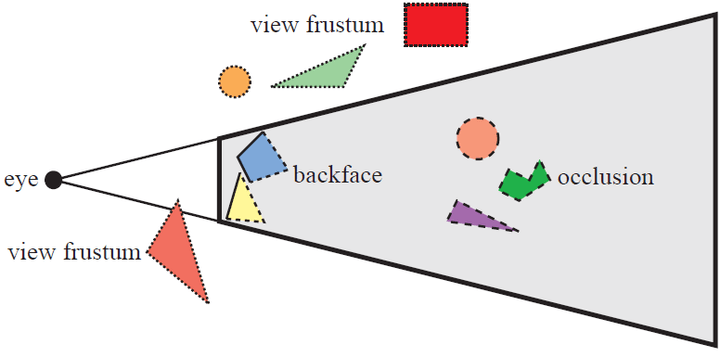

Frustum culling is a solution to this problem wherein we identify which primitives are actually relevant to the current view by performing intersection checks against the view frustum. The diagram below shows an example of this, with objects lying outside the view frustum being outlined with a dotted stroke (and labelled with “view frustum”).

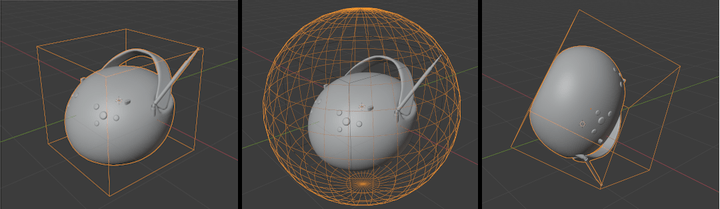

There are actually quite a few different ways to solve this problem and as always they come with various benefits and drawbacks. The first choice you’ll need to make is how you want to represent the bounds of your meshes, as testing the raw geometry against your frustum isn’t feasible, so you’d just be re-implementing vertex shading on the CPU. Therefore we need to use a simplified geometry instead, with the two most common choices being bounding spheres or oriented bounding boxes (OBBs). Usually axis aligned bounding boxes (AABBs) in model space are used to calculate the OBBs. Below is an example of an AABB, bounding sphere and OBB for our boombox.

The simplicity of a sphere means that intersection tests against other primitives are simple and cheap. Spheres also have an extremely compact data representation, requiring only a position and radius. On the other hand, the quality of spheres as bounding volumes drops quickly as the objects they enclose become “longer”. If an object’s bounds extend much further along one axis than they do in others, then the volume will contain mostly empty space, meaning that it may pass our test despite all of the actual geometry lying outside the frustum.

An alternative is to use boxes, which are much better suited to objects that do not have roughly equal maximal extents, since they store the distance from the center along each axis. An axis aligned bounding box (AABB) is the simplest version, where the edges of the box are aligned with our coordinate axes. Oriented bounding boxes are a bit more complicated in that they can have arbitrary orientation. AABBs are commonly used to represent the bounding volume in model space, while OBBs are used to represent the bounds after the object is transformed to World or View space. OBBs have almost the opposite trade-offs to spheres. For instance, their representation requires storing either all eight vertices or the three vectors that run alongside the edges of the box. Intersection tests are more expensive. However, as mentioned, they can be a much “tighter” fit for arbitrary geometry.

Which volume you use in the end depends on how accurate vs how fast you need your frustum culling to be. Some games will break culling down into broad and fine phases, so that the first broad phase can use spheres and the fine phase uses other geometry (or other culling techniques altogether). I ended up choosing OBBs because as demonstrated below, we can actually choose a very simple intersection test for the specific task of view frustum culling.

OBB Culling

We can exploit the fact that in clip space, all points lying inside the view frustum will satisfy the following inequalities:

As a quick reminder, points can be transformed from model to clip space using a Model-View-Projection (MVP) matrix. This means that we’ll need to transform all of the vertices of our AABBs into clip space.

In my implementation, the output of the culling is a list of ids for the objects I want to render. The input is the camera, and then for each object a model-to-world transform plus a model space AABB. The culling function looks like:

struct Camera {

mat4 view;

mat4 projection;

// Some other stuff!

}

struct AABB {

vec3 min = {};

vec3 max = {};

}

void cull_AABBs_against_frustum(

const Camera& camera,

const Array<mat4>& transforms,

const Array<AABB>& aabb_list,

Array<u32>& out_visible_list

) {

mat4 VP = camera.projection * camera.view;

for (size_t i = 0; i < aabb_list.size; i++) {

// model->view->projection transform

mat4 MVP = VP * transforms[i];

const AABB& aabb = aabb_list[i];

if (test_AABB_against_frustum(MVP, aabb)) {

out_visible_list.push_back(i);

}

}

}The visibility test is simple: we use our AABB corners (min and max) to initialize eight vertices, then transform each one to clip space and then perform our test as defined above:

bool test_AABB_against_frustum(mat4& MVP, const AABB& aabb)

{

// Use our min max to define eight corners

vec4 corners[8] = {

{aabb.min.x, aabb.min.y, aabb.min.z, 1.0}, // x y z

{aabb.max.x, aabb.min.y, aabb.min.z, 1.0}, // X y z

{aabb.min.x, aabb.max.y, aabb.min.z, 1.0}, // x Y z

{aabb.max.x, aabb.max.y, aabb.min.z, 1.0}, // X Y z

{aabb.min.x, aabb.min.y, aabb.max.z, 1.0}, // x y Z

{aabb.max.x, aabb.min.y, aabb.max.z, 1.0}, // X y Z

{aabb.min.x, aabb.max.y, aabb.max.z, 1.0}, // x Y Z

{aabb.max.x, aabb.max.y, aabb.max.z, 1.0}, // X Y Z

};

bool inside = false;

for (size_t corner_idx = 0; corner_idx < ARRAY_SIZE(corners); corner_idx++) {

// Transform vertex

vec4 corner = MVP * corners[corner_idx];

// Check vertex against clip space bounds

inside = inside ||

within(-corner.w, corner.x, corner.w) &&

within(-corner.w, corner.y, corner.w) &&

within(0.0f, corner.z, corner.w);

}

return inside;

}With this, we now have a working version of frustum culling! Re-running the same test from earlier, let’s examine the differences in performance, with rough timings in the table below:

| Task | Timing (ms) |

|---|---|

| Frustum Culling | 1.2 |

| CPU Command Buffer Creation + Submission | 1.5 |

| GPU execution | 1.5 |

| Total | 4.2 |

We can see that although we’ve added an extra step, we’ve saved some time while recording and submitting our command buffer. Our CPU frame time has gone up a little as a result. However, the GPU execution has decreased by about 4.3 ms! That’s an almost 75% decrease in frametime. Additionally, if we look at GPU timeline and occupancy, we see huge gains, with the render time reduced to 2.455 ms. Below is the occupancy graph, notice how much less unused vertex shader work there is.

Further Optimization

We’ve already improved our timing by about 33%, but we’re now spending a significant percentage of our frame time culling these objects. At this point, we could attempt several different optimizations (all of which could be potentially combined):

- Introducing acceleration structures that let us cull entire groupings of objects at once (as mentioned previously, bounding volume hierarchies are commonly used). In theory, culling time no longer increases linearly as a function of the number of AABBs.

- Spreading our culling across many different threads/cores, having each core process a subset of objects at the same time.

- “Vectorize” our code, taking advantage of data level parallelism and SIMD.

Each option comes with it’s own set of tradeoffs, which is almost always the case. Building acceleration structures is not free and will add it’s own line item to our per-frame timing summary. To reduce the cost, the scene is often split into static and non-static hierarchies, with the static BVH only being built once outside the frame loop, but the non-static BVH will still require updating per frame. Additionally, care must be taken when building tree data structures so we don’t end up making the culling process slower due to CPU cache misses when traversing down the tree. If your scene is mostly static, then it might make sense to build a BVH for static objects, flatten it to minimize cache misses, and then simply linearly loop through your dynamic objects as we’ve done here. Frostbite actually presented a case where removing their BVH and replacing it with a naive linear array resulted in a 3x improvement in speed.

Meanwhile, introducing multi-threading is not trivial and can easily make the entire process slower. I actually played around with using FiberTaskingLib to launch tasks that culled 1024 objects each and then combined their results into a single visibility list that my renderer could consume as before, and it was almost 10 times slower than the naive approach I showed earlier! I still have to investigate why exactly this was the case, but my bet is that it’s mostly due to the combine step. It’s possible that producing a single list will always eat into any gains made from splitting up the culling, but like I said, further investigation is needed.

Finally, let me introduce data level parallelism. The idea here is that even on a single core, CPUs have large registers that we can treat as containing multiple data points upon which we can perform the same instruction across all that data simultaneously. This idea of executing a single instruction across multiple data (or SIMD) can lead to a multiplicative speed increase. As an example, consider the following (somewhat contrived) scalarized code that takes the dot product of elements in two lists of vectors:

struct vec4 {

float x;

float y;

float z;

float w;

};

vec4 a[N] = { ... };

vec4 b[N] = { ... };

float c[N]{};

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

const vec4& lhs = a[i];

const vec4& rhs = b[i];

float res = 0.0f;

// This is probably actually an inlined function call or something

for (size_t j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

res += lhs[j] * rhs[j];

}

c[i] = res;

}Now let’s consider how we could “vectorize” this code. Modern SIMD registers can store anywhere from 128 to 512 bits of data, which means we could operate on sets of 4 to 16 32-bit floating point numbers at a time. For the purposes of this example, we’ll use 128-bit wide registers (e.g. ones with 4 “lanes”) but the idea extends to higher width registers trivially. So instead of storing our data as an array of structs (commonly referred to as AoS), let’s use a structure of arrays (SoA) to represent our list of vectors. This means instead of storing our vectors in a way that looks like:

x y z w x y z w x y z w ...We’ll store each component in their own list, so it’ll look more like:

x x x x x x ...

y y y y y y ...

z z z z z z ...

w w w w w w ...Here’s some C++ code (that I didn’t attempt to compile) that shows this alternate structure:

struct VectorList {

float* x;

float* y;

float* z;

float* w;

// Probably additional info on how big it is, etc

size_t size;

}Next, instead of loading our data one vector at a time, we’ll load the data into our SIMD registers. To do so, we’ll have to use “intrinsics” provided by your CPU manufacturer, which in my case is Intel. I have no idea what the situation is on AMD, but I know that ARM64 and other platforms probably provide their own set of intrinsics. For Intel, an exhaustive (if not particularly beginner friendly) list can be found on their intrinsics guide. So we’ll be using these intrinsics to load our data into 128-bit wide registers, and multiply and add across the lanes to calculate 4 dot products all at once. I have found it helpful to visualize these operations vertically due to the nature of how SIMD operates across the “lanes” of SIMD registers, so I’ve annotated the code with crappy little diagrams to try and visualize the intrinsics:

VectorList a{N};

VectorList b{N};

float c[N]{};

// We iterate with a stride of 4

constexpr size_t stride = sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float); // 4

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; i += stride) {

// Load the x component of 4 vectors into a SIMD register

__m128 x_lhs = _mm_load_ps(&a.x[i]);

__m128 x_rhs = _mm_load_ps(&b.x[i]);

// Do the same for our other components

__m128 y_lhs = _mm_load_ps(&a.y[i]);

__m128 y_rhs = _mm_load_ps(&b.y[i]);

__m128 z_lhs = _mm_load_ps(&a.z[i]);

__m128 z_rhs = _mm_load_ps(&b.z[i]);

__m128 w_lhs = _mm_load_ps(&a.w[i]);

__m128 w_rhs = _mm_load_ps(&b.w[i]);

// Now multiply the x components together:

// Equivalent to

// x1 x2 x3 x4

// * * * *

// X1 X2 X3 X4

// = = = =

// r1 r2 r3 r4

__m128 res = _mm_mul_ps(x_lhs, x_rhs);

// Now, multiply the other components together AND add the result to our temp variable

// Equivalent to

// y1 y2 y3 y4

// * * * *

// Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4

// + + + +

// r1 r2 r3 r4

// = = = =

// r1 r2 r3 r4

res = _mm_fmadd_ps(y_lhs, y_rhs, res);

res = _mm_fmadd_ps(z_lhs, z_rhs, res);

res = _mm_fmadd_ps(w_lhs, w_rhs, res);

// Store the data into our array c

// This copies all 4 dot products into our array at index i through i+3

_mm_store_ps(&c[i], res);

}A few things stuck out to me. First of all, we had to change the way our data was laid out in memory in order to take advantage of our SIMD lanes, so re-writing an algorithm might mean you need to make more fundamental changes than just swapping out your inner for loops. Additionally, those intrinsic functions are a bit scary in terms of how they are platform specific. This can be addressed by using a SIMD library or something like DirectXMath, which takes care of using the relevant intrinsics for most CPU vendors. Finally, you might feel like writing such code comes with a significant cognative and productivity tax. There are also tools like ISPC that make writing vectorized code a bit less “artisinal”, but I haven’t had a chance to really play around with them. I should also mention that compilers are sometimes able to translate scalarized code into vectorized code, but since I was aiming to write SIMD code as a learning exercise I didn’t look into it very much.

Let’s look at a less contrived example: frustum culling! That is, after all, the whole point of this post.

SIMD Implementation

When I started looking into how we could re-write this into SIMD, I actually found a series of blog posts on optimizing frustum culling by Arseny Kapoulkine. However, the series is specifically about optimizing it on the Playstation 3 (I think) and as a result it uses the SPU intrinsics that were part of Sony’s/IBM’s platform. But I was able to effectively translate it to use intel’s SSE/AVX intrinsics with only one or two problems.

There were two different operations I figured was worth exploiting SIMD for:

- Multiplying the various transformation matrices, since that’s done for each object and their 4x4 nature is a natural fit for SIMD lanes

- Transforming our model space AABB vertices to clip space

First, let’s tackle matrix multiplication for 4x4 matrices. The biggest thing I struggled with on this one was understanding how we can calculate an entire row of our resulting matrix at once. Let’s start by considering how we’d calculate the th row of our matrix for :

You may already notice the pattern in the “columns” above, but just to make it super clear, let’s flip this over onto its side:

Hopefully that helps you visualize how we can use SIMD lanes for this problem. We’ll have to fill several registers such that they contain only a single element of the ith row of , then perform the multiplications & adds that we’ve already demonstrated. Let’s look at the code:

struct mat4 {

union {

vec4 rows[4];

float data[16];

}

}

void matrix_mul_sse(const mat4& A, const mat4& B, mat4& dest)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE(A.rows); i++) {

// Fill up our registers with a component from the ith row of A

__m128 A_i0 = _mm_broadcast_ss((&A.rows[i].x));

__m128 A_i1 = _mm_broadcast_ss((&A.rows[i].y));

__m128 A_i2 = _mm_broadcast_ss((&A.rows[i].z));

__m128 A_i3 = _mm_broadcast_ss((&A.rows[i].w));

// First multiply, then add

__m128 res = _mm_mul_ps(v_x, _mm_load_ps((&B.rows[0].x)));

res = _mm_fmadd_ps(v_y, _mm_load_ps((&B.rows[1].x)), res);

res = _mm_fmadd_ps(v_z, _mm_load_ps((&B.rows[2].x)), res);

res = _mm_fmadd_ps(v_w, _mm_load_ps((&B.rows[3].x)), res);

_mm_store_ps((&dest.rows[i].x), v_x);

}

};Next up, we need to write code that will transform our AABB vertices into clip space. To accomplish this we could use either 128-bit or 256-bit wide registers. Since we have 8 vertices, it would probably make sense to use the 8 lanes available with 256-bit. I ended up writing a 128-bit version first, and then a 256 version, and neither showed any speed differences on my machine.

Performing the matrix-vector multiplication is nearly identical to our matrix multiplication from earlier. The operation looks like:

So for each component we’ll need to perform 4 multiply and 3 adds, plus splatting of the various components of our transform matrix. It ends up being pretty compact:

void transform_points_8(__m256 dest[4], const __m256 x, const __m256 y, const __m256 z, const mat4& transform)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < 4; ++i) {

__m256 res = _mm256_broadcast_ss(&transform.rows[i].w);

res = _mm256_fmadd_ps(_mm256_broadcast_ss(&transform.rows[i].x), x, res);

res = _mm256_fmadd_ps(_mm256_broadcast_ss(&transform.rows[i].y), y, res);

res = _mm256_fmadd_ps(_mm256_broadcast_ss(&transform.rows[i].z), z, res);

dest[i] = res;

}

}Finally, we can bring this all together by filling registers with our unique combinations of the AABB’s min and max components, transforming those vertices, performing logical comparisons and then finally reducing the result into a single value. We don’t care how many vertices are in or out, just whether any single vertex is inside.

// Fills an entire __m128 with the value at c of the __m128 v

#define SPLAT(v, c) _mm_permute_ps(v, _MM_SHUFFLE(c, c, c, c))

bool test_AABB_against_frustum_256(mat4& transform, const AABB& aabb)

{

// Could probably skip this by storing our AABBs as 2 vec4s just for alignment's sake

vec4 min{ aabb.min, 1.0f };

vec4 max{ aabb.max, 1.0f };

const __m128 aabb_min = _mm_load_ps(&min.x);

const __m128 aabb_max = _mm_load_ps(&max.x);

// We have to do some shuffling to get our combinations

// res = _mm_shuffle_ps(a, b, _MM_SHUFFLE(i, j, k, l)) is equivalent to

// res[0] = a[i]

// res[1] = a[j]

// res[2] = b[k]

// res[3] = b[l]

__m128 x_minmax = _mm_shuffle_ps(aabb_min, aabb_max, _MM_SHUFFLE(0, 0, 0, 0)); // x x X X

x_minmax = _mm_permute_ps(x_minmax, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 0, 2, 0)); // x X x X

const __m128 y_minmax = _mm_shuffle_ps(aabb_min, aabb_max, _MM_SHUFFLE(1, 1, 1, 1)); // y y Y Y

const __m128 z_min = SPLAT(aabb_min, 2); // z z z z

const __m128 z_max = SPLAT(aabb_max, 2); // Z Z Z Z

// Each __m256 represents a single component of 8 vertices

// _mm256_set_m128 just combines two m128s into a single m256

const __m256 x = _mm256_set_m128(x_minmax, x_minmax);

const __m256 y = _mm256_set_m128(y_minmax, y_minmax);

const __m256 z = _mm256_set_m128(z_min, z_max);

// corner_comps[0] = { x1, x2, x3, ... } ... corners[4] = {w1, w2, w3, w4 ...};

__m256 corner_comps[4];

transform_points_8(corner_comps, x, y, z, transform);

const __m256 neg_ws = _mm256_sub_ps(_mm256_setzero_ps(), corner_comps[3]);

// Test whether -w < x < w

// Note that the comparison intrinsics will set the lanes to either 0 or 0xFFFFFFFF

__m256 inside = _mm256_and_ps(

_mm256_cmp_ps(neg_ws, corner_comps[0], _CMP_LE_OQ),

_mm256_cmp_ps(corner_comps[0], corner_comps[3], _CMP_LE_OQ)

);

// inside && -w < y < w

inside = _mm256_and_ps(

inside,

_mm256_and_ps(

_mm256_cmp_ps(neg_ws, corner_comps[1], _CMP_LE_OQ),

_mm256_cmp_ps(corner_comps[1], corner_comps[3], _CMP_LE_OQ)

)

);

// inside && 0 < z < w

inside = _mm256_and_ps(

inside,

_mm256_and_ps(

_mm256_cmp_ps(neg_ws, corner_comps[2], _CMP_LE_OQ),

_mm256_cmp_ps(corner_comps[2], corner_comps[3], _CMP_LE_OQ)

)

);

// Reduce our 8 different in/out lanes to 4

// _mm256_extractf128_ps will extract four lanes into an m128 (either the first four or second four)

__m128 reduction = _mm_or_ps(_mm256_extractf128_ps(inside, 0), _mm256_extractf128_ps(inside, 1));

// Keep reducing! The following is equivalent to

// { inside[0] || inside[2], inside[1] || inside[3], inside[2] || inside[2], inside[3] || inside[3] }

reduction = _mm_or_ps(reduction, _mm_permute_ps(reduction, _MM_SHUFFLE(2, 3, 2, 3)));

// Then we perform another OR to fill the lowest lane with the final reduction

// { (reduction[0] || reduction[2]) || (reduction[1] || reduction[3]), ... }

reduction = _mm_or_ps(reduction, _mm_permute_ps(reduction, _MM_SHUFFLE(1, 1, 1, 1)));

// Store our reduction

u32 res = 0u;

_mm_store_ss(reinterpret_cast<float*>(&res), reduction);

return res != 0;

}It’s definitely not the nicest looking code, but it’ll be worth it, I promise. Once you get used to the intrinsics, it’s really not so bad. This thing I had the most trouble with was definitely just parsing the documentation — there are a LOT of intrinsics, and discovering the one you need is not easy since the search is only helpful if you know or can guess the name of the one you need.

Another operation that puzzled me was how to best perform the “horizontal” OR reduction at the end. In zeux’s examples, he uses an orx intrinsic that doesn’t appear to exist on intel. Instead, I reduced by shuffling/permuting the vectors to ensure the first component ends up holding the final value we want.

Now let’s take a look at the results:

| Task | Timing (ms) |

|---|---|

| Frustum Culling | 0.3 |

| CPU Command Buffer Creation + Submission | 1.5 |

| GPU execution | 1.5 |

| Total | 3.3 |

The time needed for culling has gone down from ~1.1 ms to ~0.3 ms! On my laptop, the gains are similar — 3.0 ms down to 0.6ms. With SIMD, we are now spending less time rendering a frame on both the CPU and the GPU.

This may seem like a lot of work for saving 0.8 ms, but keep in mind that we may want to perform frustum culling many times — for instance, each dynamic shadow will have it’s own frustum(s), and we definitely don’t want to waste time submitting more draw calls than necessary there. So these optimizations will have a multiplicative effect as you add more shadow maps.

Conclusion

To recap, for our contrived example we’ve brought down our frame time from 8.2 ms to 3.3 ms with frustum culling. Introducing SIMD in a small part of the code was also pretty impactful, cutting down the cost of culling by about 75%. There is probably still significant headroom for improvement — the lower bound is likely going to be determined by the bandwidth limitations around writing to our visibility list. Currently, we’re reaching about 32 bits * 1e4 / 3.0e-4s ~= 1e9 bits/s ~= 1 GB/s in this worst case.

Additionally, I just want to re-iterate that I am not experienced with SIMD intrinsics. If you know of a better way to perform any parts of the above, please let me know in the comments, by email or through twitter @BruOps.

There is also a subtle problem with my culling code. If the OBB is large compared to the view frustum, then this code will produce false negatives. We should probably also perform the reciprocal test and check whether any of the frustum corners fall within the OBB. This is really only a problem at the near plane, so we might be able to get away with just testing those four corners.

Finally, I just want to highlight that while profiling with PIX I encountered pretty high variability in CPU execution times. I expected CPU timings to vary by 10-20% but I often had events exhibit single frame “spikes” where execution times were orders of magnitude higher than usual (within a capture of a few seconds). Other times, there would be smaller spikes that were only 2-5 times larger. Taking a look at the timeline, I saw that in these cases the thread my code was running on would stall, but it seems pretty non-deterministic since it’d happen for a few frames, and then wouldn’t. The camera wasn’t moving at all during the recordings, and as far as I know there were no allocations during the frame, so I’m not sure what was causing the variability between frames.

Thanks for reading til the end! Shout out to the folks on the Graphics Programming discord who provided guidance and rubber ducking. I hope you and your loved ones have a happy holiday, and that 2021 is kinder to us all.

Comments powered by Talkyard.